Resonate is pioneering a novel programming model to distributed computing called Distributed Async Await. Distributed Async Await is an extension of traditional async await that goes beyond the boundaries of a single process and makes distributed computing a first-class citizen.

Given that Distributed Async Await is an extension of async await, I figured a blog post exploring the mechanics of functions, promises, and the event loop would be fun.

This post explores the mechanics of async await using Elixir. Elixir's concurrency model offers an excellent platform for implementing the mechanics of async await. However, the approach outlined here is not intended as a guideline for Elixir application development.

The Code on GitHub

Introduction

Many of us were first introduced to async await when we learned JavaScript. Because JavaScript offers one of the most popular implementations, this introduction often shapes our understanding of async await, leading us to conflate the fundamental principles of the asynchronous programming model with the specific implementation decisions made by JavaScript.

The most common misconceptions are that async await necessitates a non-blocking, single-threaded runtime. JavaScript's runtime is non-blocking primarily because it is single-threaded. However, asynchronous programming models can be implemented as both single-threaded and multi-threaded runtimes, and they can be implemented as non-blocking or blocking.

From Sync to Async

The journey from synchronous to asynchronous programming is a shift from sequential to concurrent execution - essentially, instead of doing one thing at a time, we do multiple things simultaneously.

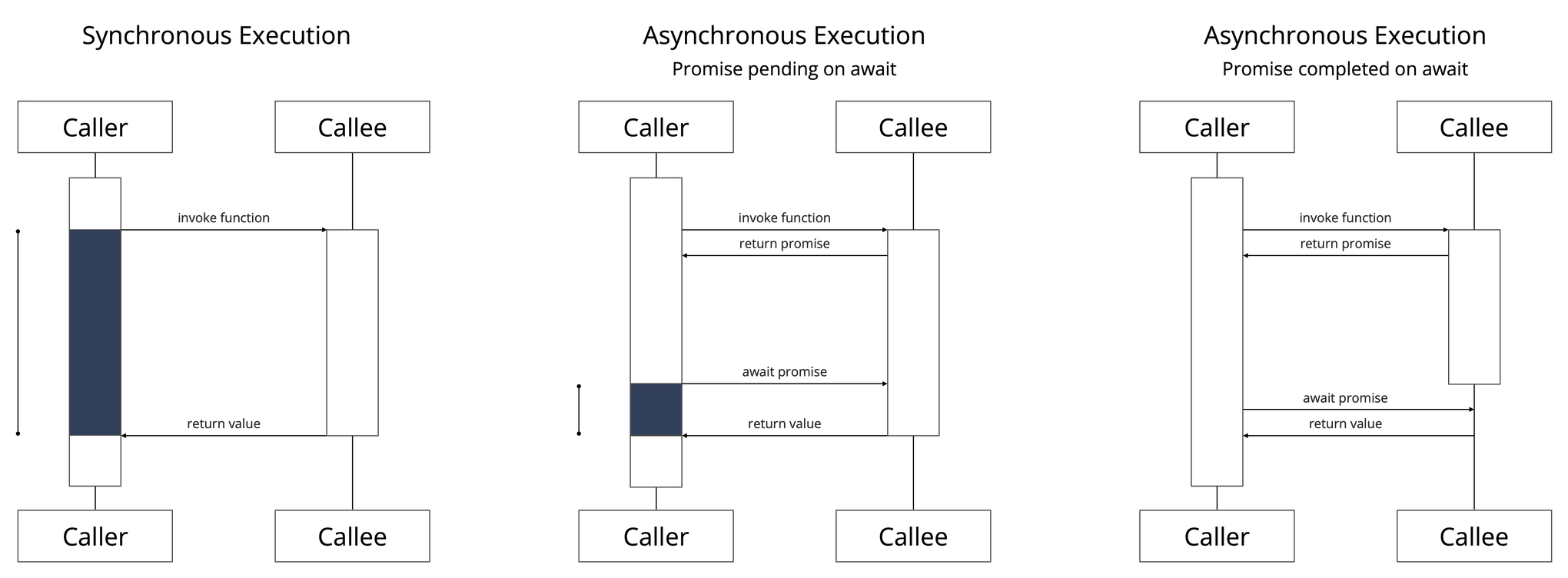

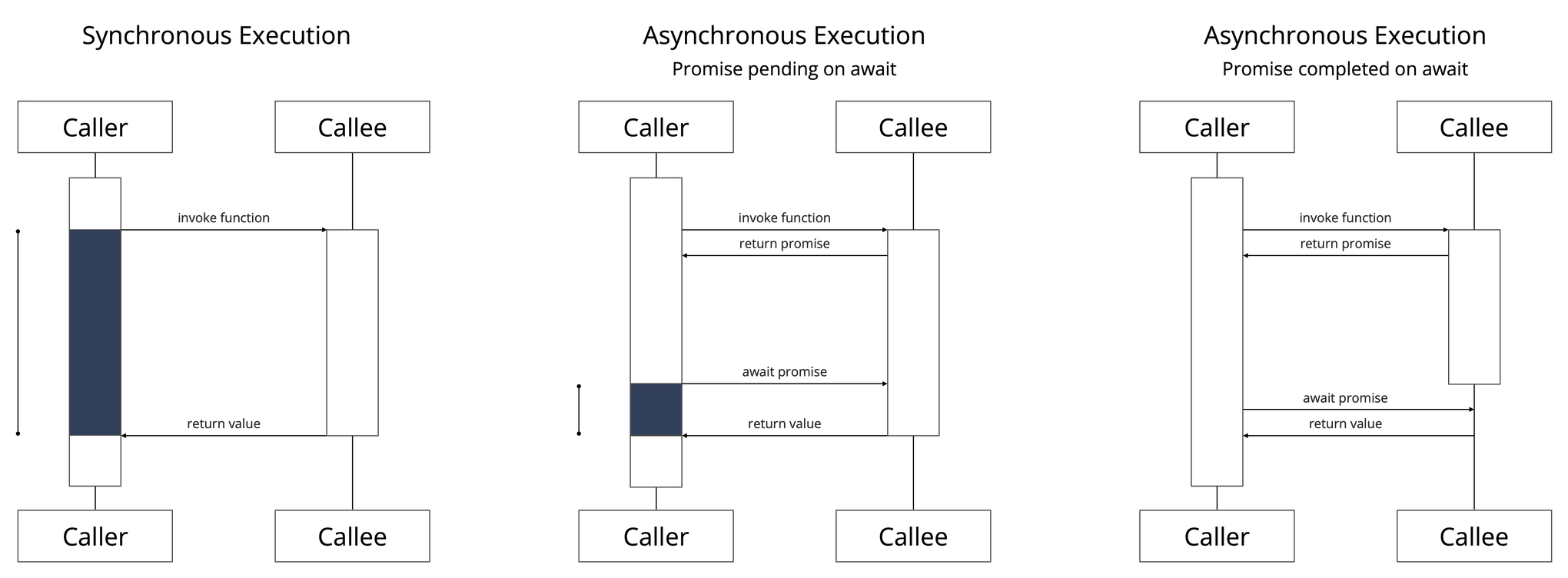

We will reason about synchronous and asynchronous programming in terms of pairs of events captured during the execution. We assume that traces contain the following events of interest:

- in synchronous programming

invoke function and return value.

- in asynchronous programming

invoke function and return promise,await promise and return value.

Synchronous Execution

A synchronous execution consists of a single round trip, one invoke-and-return-value interaction between the caller and callee. The caller suspends its execution until the callee completes its execution and returns a value (Figure 1., left).

Asynchronous Execution & Promises

An asynchronous execution consists of two round trips, one invoke-and-return-promise interaction and one await-and-return-value interaction between the caller and the callee.

A promise can either be interpreted as a representation of the callee or as a representation of a future value. A promise is either pending, indicating that the callee is in progress and has not returned a value, or completed, indicating that the callee terminated and has retuned a value.

If the promise is pending on await, the callers suspends its execution until the callee completes its execution and returns a value (Figure 1., center). If the promise is completed on await, the caller continues with the returned value (Figure 1., right).

The Event Loop

The runtime of async await is referred to as an Event Loop. An Event Loop is a scheduler that allows an asynchronous execution to register interest in a specific event. (In this blog we are only interested in the completion of a promise). Once registered, the execution suspends itself. When a promise completes, the Event Loop resumes the execution.

For the remainder of this blog, we will implement async await facilities and an Event Loop in Elixir. Why Elixir? For starters, mapping async await to Elixir is straightforward, making the implementation an excellent illustration. More importantly, mapping async await to Elixir allows us to dispel the common myth that async await is intrinsically non-blocking: by mapping asynchronous executions onto Elixir processes and deliberately blocking the process when awaiting a promise.

Elixir Crash Course

Elixir is a dynamically typed, functional programming language that runs on the Erlang virtual machine (BEAM).

Elixir's core abstraction is the process, an independent unit of execution with a unique identifier. self() yields the identifier of the current process. All code executes in the context of a process. Elixir processes execute concurrently, with each process executing its instructions sequentially.

# Create a new process - You can use the Process Identifier to send messages to the process

pid = spawn(fn ->

# This block of code will execute in a separate process

end)

Processes communicate and coordinate by exchanging messages. Sending a message is a non-blocking operation, allowing the process to continue execution.

# Send a message to the process with identifier pid (non-blocking operation)

send(pid, {:Hello, "World"})

Conversely, receiving a message is a blocking operation, the process will suspend its execution until a matching message arrives.

# Receive a message (blocking operation)

receive do

{:Hello, name} ->

IO.puts("Hello, #{name}!")

end

Arguably the most popular abstraction is a GenServer. A GenServer is a process like any other Elixir process. A GenServer abstracts the boilerplate code needed to build a stateful server.

defmodule Counter do

use GenServer

# Client API

# Starts the GenServer

def start_link() do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, 0, name: __MODULE__)

end

# Synchronous call to get the current counter value

def value do

GenServer.call(__MODULE__, :value)

end

# Asynchronous call to increment the counter

def increment do

GenServer.cast(__MODULE__, :increment)

end

# Server Callbacks

# Initializes the GenServer with the initial value

def init(value) do

{:ok, value}

end

# Handles synchronous calls

def handle_call(:value, _from, state) do

{:reply, state, state}

end

# Handles asynchronous messages

def handle_cast(:increment, state) do

{:noreply, state + 1}

end

end

Async Await in Elixir

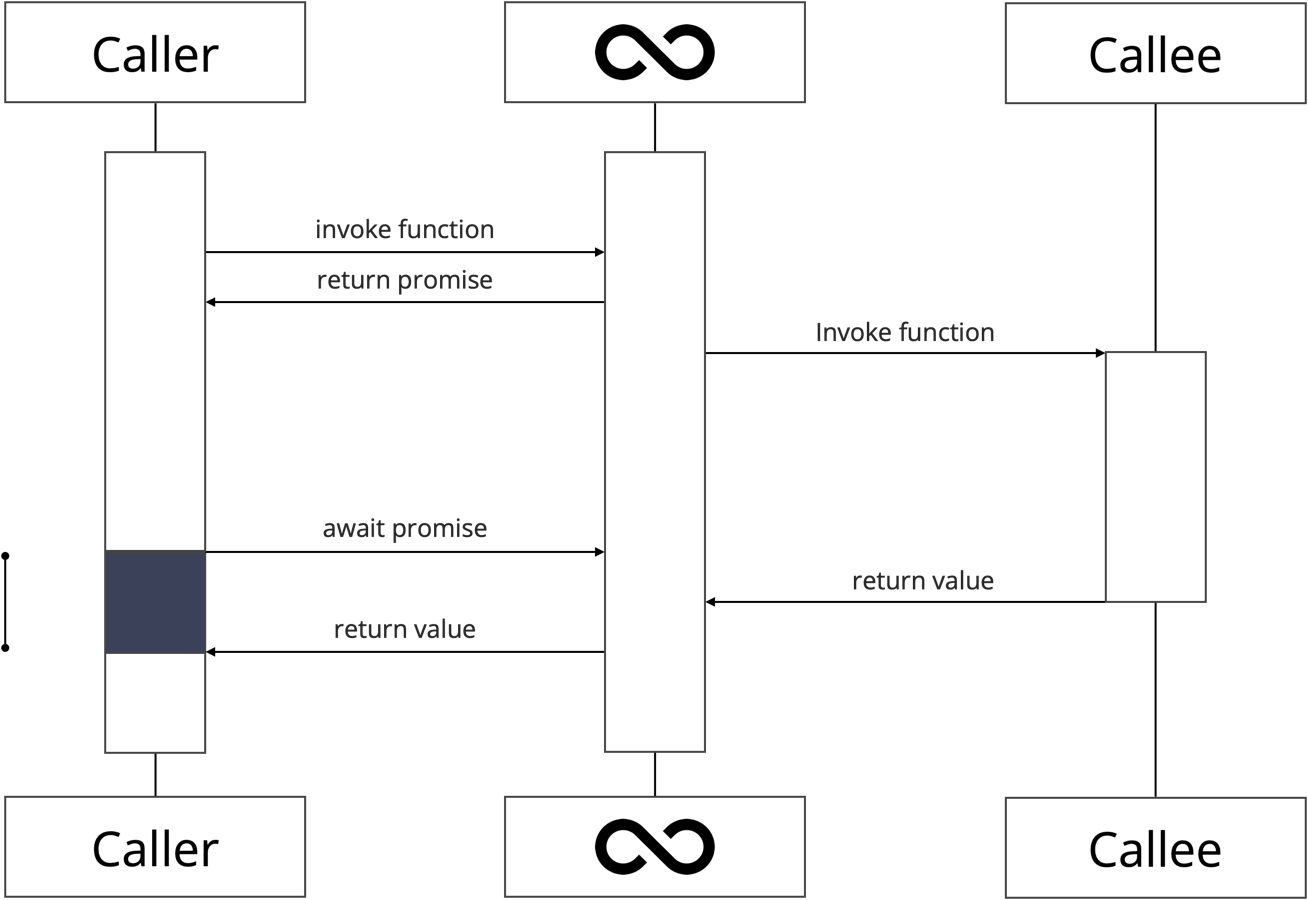

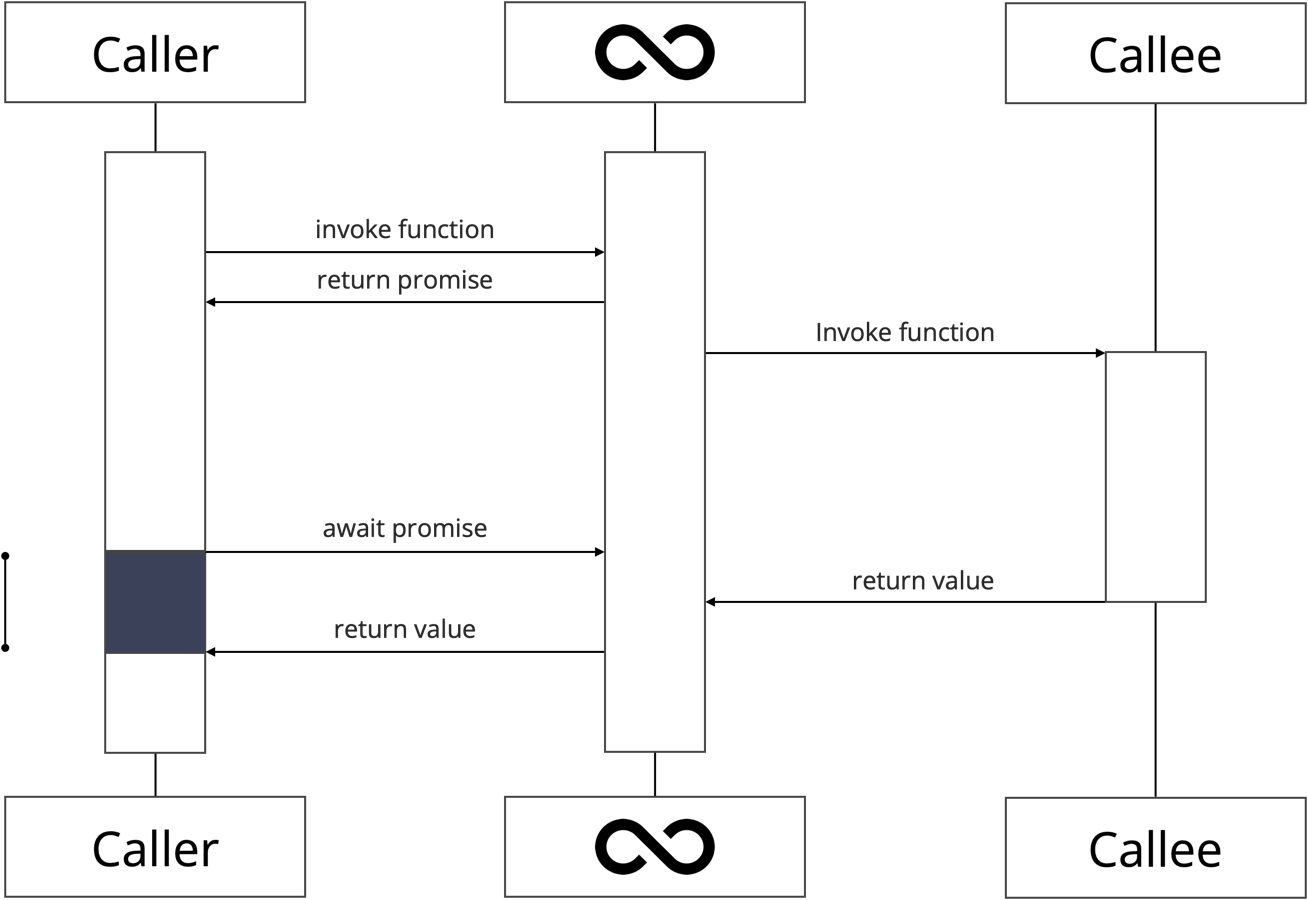

The Async Await Module allows the developer to express the concurernt structure of a computation while the Event Loop Module implements the concurrent structure of a computation.

We will map an asynchronous execution of a function on an Elixir process executing the function. We will use the identifier, the pid, of the process to refer to the execution and the promise representing the execution.

Our goal is to run something like this:

# outer refers to the pid of the outer Elixir process

outer = Async.invoke(fn ->

# inner refers to the pid of the inner Elixir Process

inner = Async.invoke(fn ->

42

end)

# We use the pid to await the inner promise

v = Async.await(inner)

2 * v

end)

# We use the pid to await the outer promise

IO.puts(Async.await(outer))

The Library

Let's start with the simple component, the library. Remember there are only two interactions, invoke a function and return a promise and await a promise and return a value. Invoke does not suspend the caller but await may suspend the caller if the promise is not yet resolved.

defmodule Async do

def invoke(func, args \\ []) do

# invoke function, return promise

# will never block the caller

GenServer.call(EventLoop, {:invoke, func, args})

end

def await(p) do

# await promise, return value

# may block the caller

GenServer.call(EventLoop, {:await, p})

end

end

In Elixir terms:

GenServer.call(EventLoop, {:invoke, func, args}) is a blocking call, however, as we will see below, the method always returns immediately, therefore, this call never suspends the caller.GenServer.call(EventLoop, {:await, p}) is a blocking call and, as we will see below, the function may not always return immediately, therefore, this call may suspend the caller.

The Event Loop

On to the more complex component, the Event Loop.

The State

The Event Loop tracks two entities: promises and awaiters.

%State{

promises: %{#PID<0.269.0> => :pending, #PID<0.270.0> => {:completed, 42}},

awaiters: %{

#PID<0.269.0> => [

# This data structure allows us to defer the response to a request

# see GenServer.reply

{#PID<0.152.0>,

[:alias | #Reference<0.0.19459.4203495588.2524250117.118052>]}

],

#PID<0.270.0> => []

}

}

Promises

promises associate a promise identifier with the status of the asynchronous execution the promise represents. The state of a promise is either

:pending, indicating the execution is still in progress, or{:completed, result}, indicating the execution terminated with result.

Awaiters

awaiters associate a promise identifier with the list of execution identifiers that are waiting for the promise to be resolved: Each pid in the list corresponds to a process that executed an await operation on the promise and is currently suspended, waiting for the promise to be fulfilled. When the promise is resolved, these awaiting processes are notified and can continue their execution with the result of the promise.

The Behavior

By tracking the current status of each async execution via promises and the dependencies between executions via awaiters, the Event Loop can orchestrate the concurrent execution of code. Three methods are all we need:

defmodule EventLoop do

use GenServer

alias State

def start_link(_opts \\ []) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, State.new(), name: __MODULE__)

end

def init(state) do

{:ok, state}

end

def handle_call({:invoke, func, args}, {caller, _} = _from, state) do

# ...

end

def handle_call({:await, promise}, {caller, _} = from, state) do

# ...

end

def handle_call({:return, callee, result}, {caller, _} = _from, state) do

# ...

end

end

Invoke

The invoke method spawns a new Elixir process and uses the process identifier, assigned to callee, as the promise identifier. The process executes the function via apply(func, args) and then calls the Event Loop's return method to return the function's result and complete the promise.

def handle_call({:invoke, func, args}, {caller, _} = _from, state) do

# Here, we are using the process id also as the promise id

callee =

spawn(fn ->

GenServer.call(EventLoop, {:return, self(), apply(func, args)})

end)

new_state =

state

|> State.add_promise(callee)

{:reply, callee, new_state}

end

Await

This is the heart and soul of our Event Loop. When we call await, we distinguish between two cases:

- If the promise is resolved, we reply to the caller immediately (not suspending the caller), returning the result.

- If the promise is pending, we do not reply to the caller immediately (suspending the caller), registering the caller as an awaiter on the promise.

def handle_call({:await, promise}, {caller, _} = from, state) do

# The central if statement

case State.get_promise(state, promise) do

# Promise pending, defer response to completion

:pending ->

new_state =

state

|> State.add_awaiter(promise, from)

{:noreply, new_state}

# Promise completed, respond immedately

{:completed, result} ->

{:reply, result, state}

end

end

Return

When a process terminates, we iterate through the list of awaiters, replying to their request (resuming the caller) returning the result. Additionally, we update the state of the promise from pending to completed.

def handle_call({:return, callee, result}, {caller, _} = _from, state) do

Enum.each(State.get_awaiter(state, callee), fn {cid, _} = caller ->

GenServer.reply(caller, result)

end)

new_state =

state

|> State.set_promise(callee, result)

{:reply, nil, new_state}

end

Running the App

Now we are ready to run the application. In case you want to reproduce the results, the code is available as an Elixir Livebook on GitHub.

IO.inspect(self())

outer = Async.invoke(fn ->

IO.inspect(self())

inner = Async.invoke(fn ->

IO.inspect(self())

42

end)

v = Async.await(inner)

2 * v

end)

IO.puts(Async.await(outer))

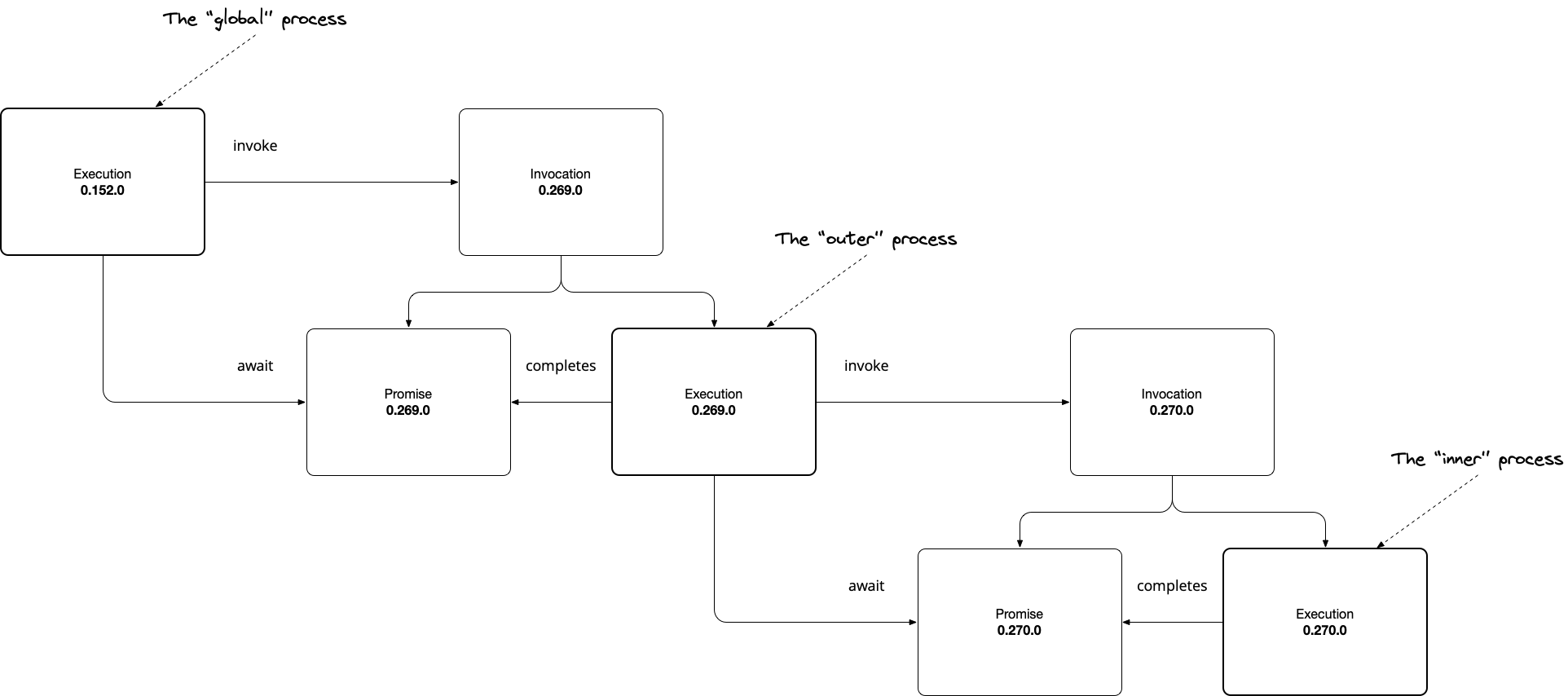

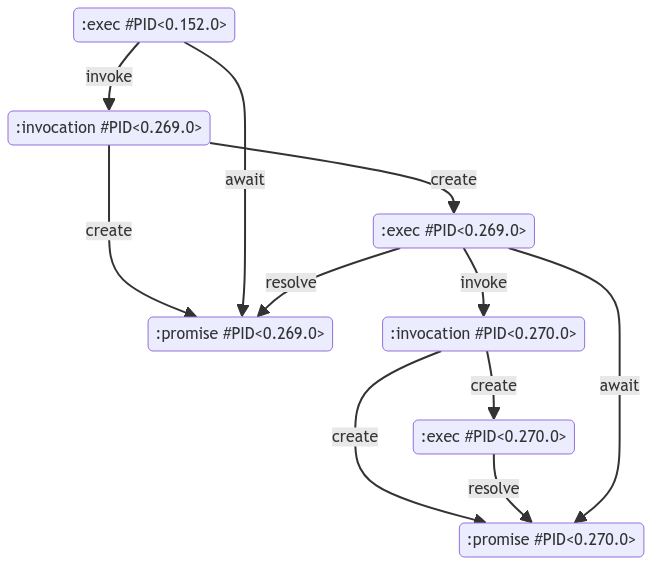

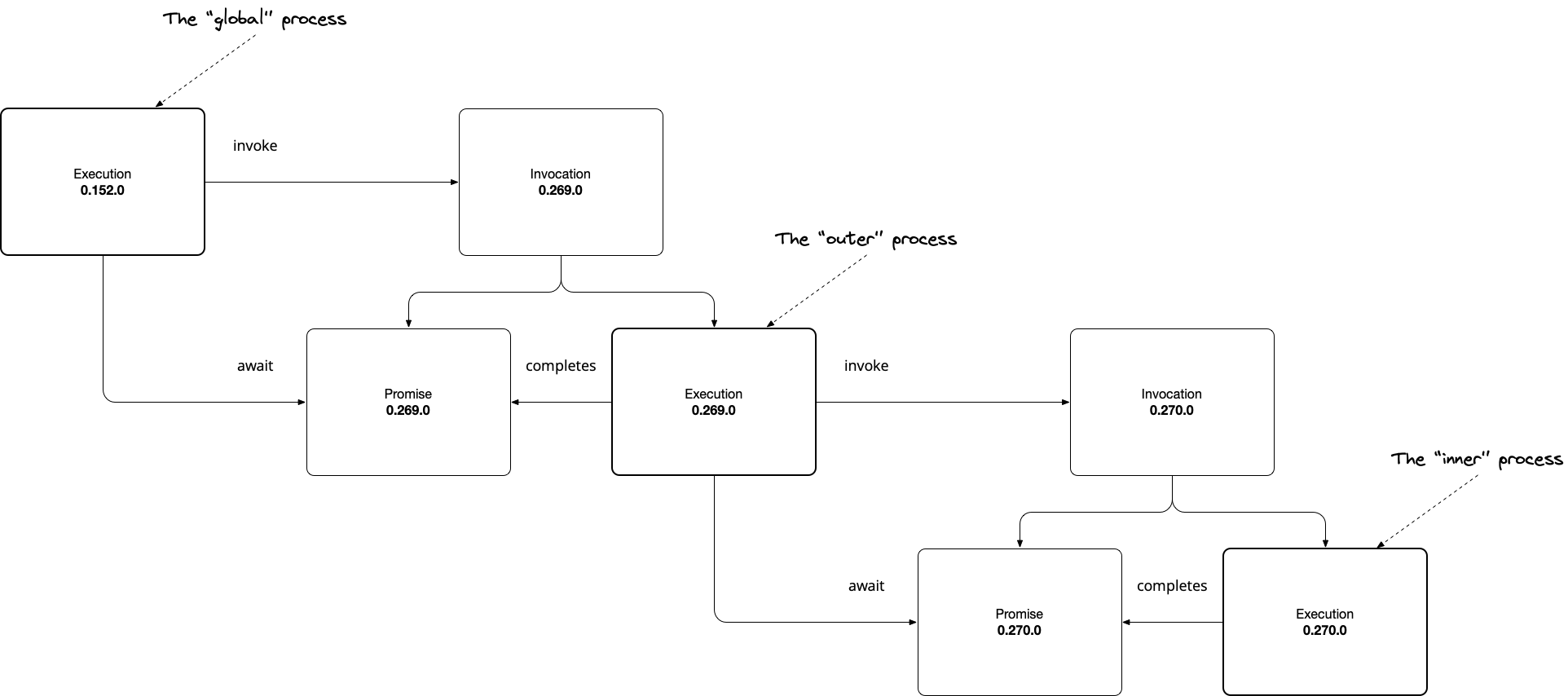

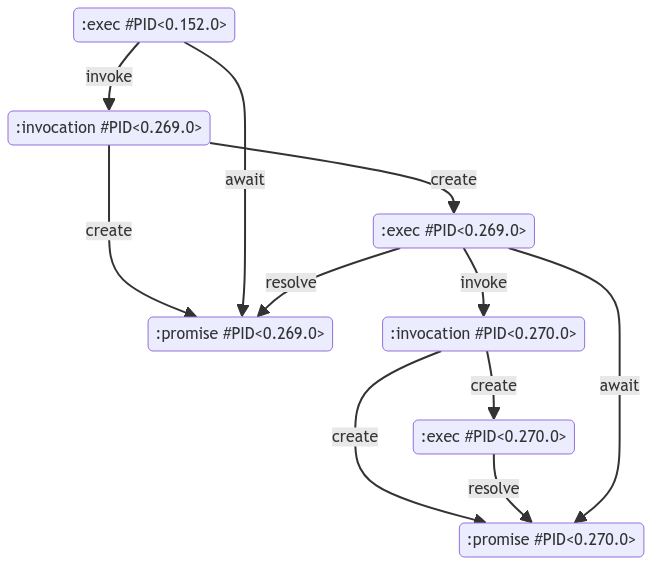

Running the application will print something like this:

#PID<0.152.0>

#PID<0.269.0>

#PID<0.270.0>

84

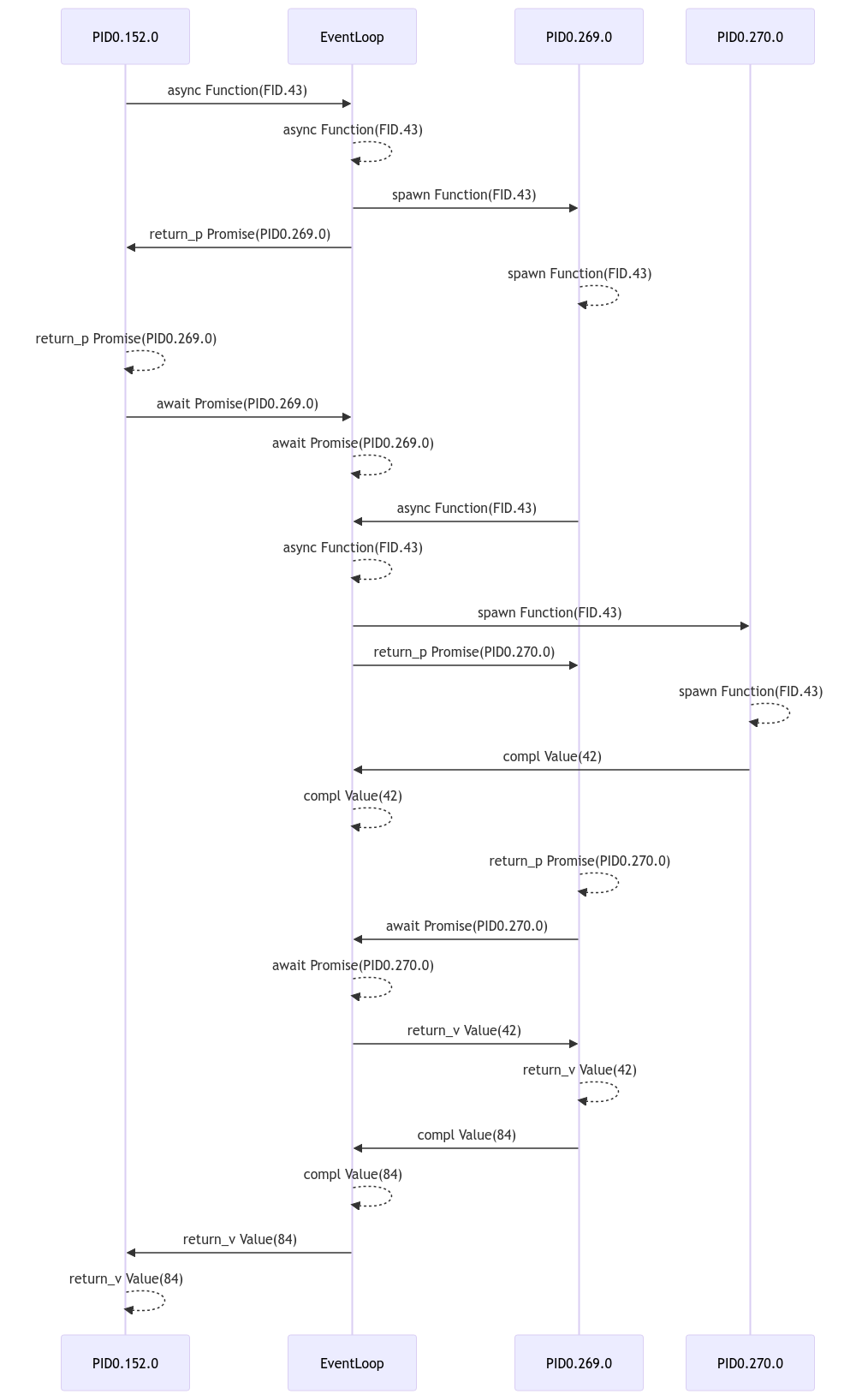

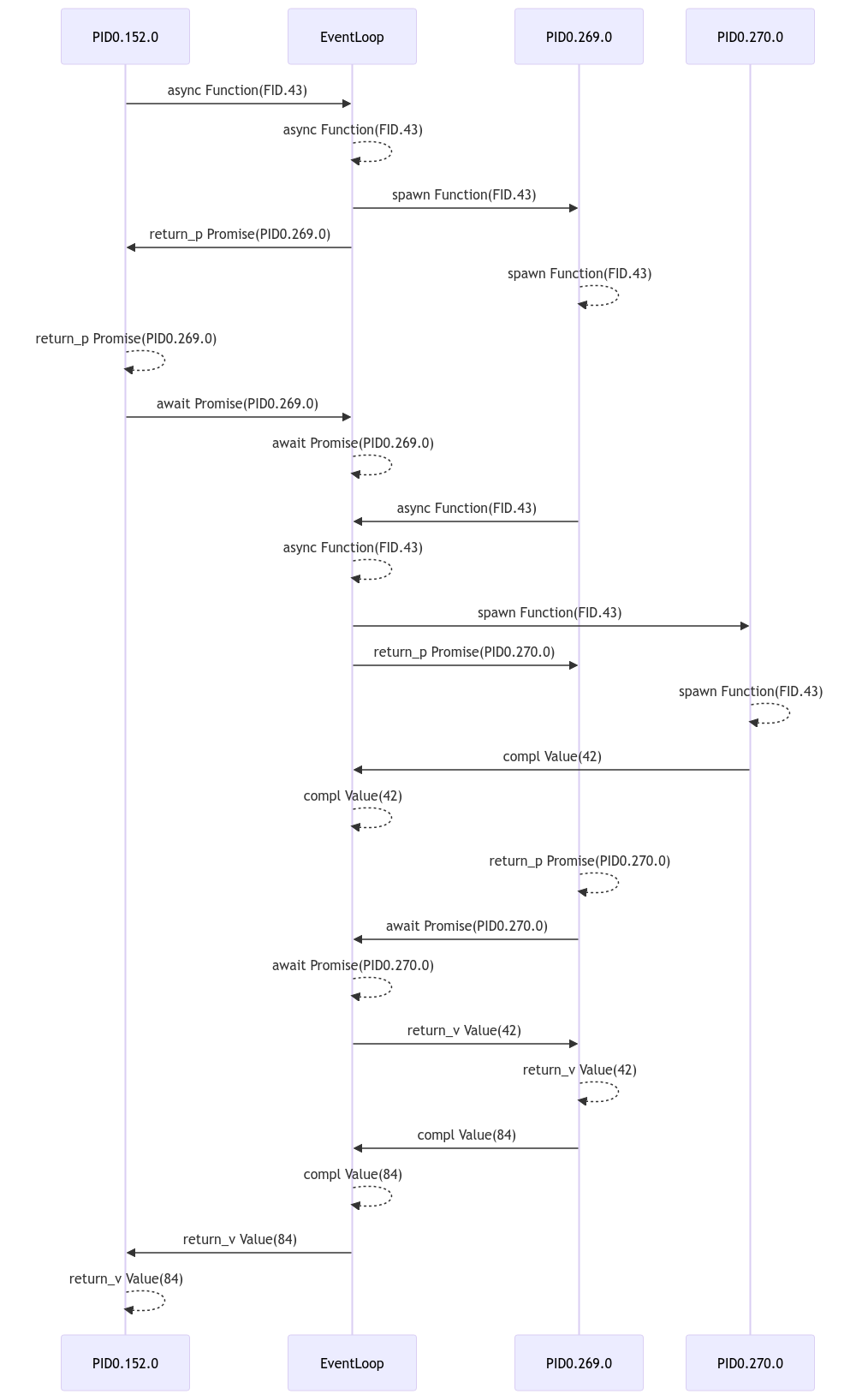

Additionally, we will get a entity diagram and a sequence diagram illustrating the structure and behavior in terms of executions and promises.

Entity Diagram

Sequence Diagram

Outlook

We explored the core mechanics of async await, but there are still more concepts to discover. For example, we could explore promise combinators such as Promise.all (wait for all promises in a list to complete) or Promise.one (wait one promise in a list to complete). Another example, we could explore promise linking, when a function doesn't return a value but returns itself a promise. These exercises are left for the reader.

Conclusion

Async await is a programming model that elevates concurrency to a first-class citizen. Async await allows the developer to express the concurrent structure of a computation while the event loop executes the computation.

If you want to explore a programming model that elevates distribution to a first-class citizen, head over to resonatehq.io and try Distributed Async Await 🏴☠️